Just from the two beginning weeks in class and the wide range of blog posts, it is clearly evident that networks play a dominant role in all of our lives. Referencing the latest post about research in the neural field, we could say that networks are “hard-wired” into our systems. Merely cataloguing some of my daily activities illustrates the important role networks play in my life. I got some exercise by running on a treadmill (a network of electrical circuits and connections), took the bus to the mall (a transportation network), and purchased some laundry detergent (a network of the chemicals that comprise the formula). This short list illustrates that networks not only take on a variety of forms, but also that they necessary components of life. A question that might arise is: what happens if a network is “shut down” for political, practical, or ethical reasons? This is the exact question addressed by the article: Kidney Exchange: A Life-Saving Application of Matching Theory.

A depiction of the kidney showing transsection of the renal artery and the renal vein as seen in a live donor transplant.

Credit: © Brian Evans

Here’s the background. In class, as well as any introduction to economics course, we learn that the market for a good is just a giant network of consumers and producers. The “bridge” in this giant network can be thought of as the price of the good or service. In a very rudimentary sense, the price serves this bridging mechanism by connecting buyers and sellers who might have otherwise not interacted. There’s no need for further review of economics to state that the price allocation mechanism is good, but far from perfect. For some goods and services, prices cannot serve as the ultimate allocative force for ethical and equity reasons. A prime example of such a “good” is a kidney. According to the article, in 2005 alone, 60,000 people will be in need of a kidney transplant while only about a quarter of those people will find a donor. The National Organ Transplant Act makes it illegal to acquire an organ for “valuable consideration,” which precludes a traditional price allocation of kidneys. It’s not necessary to go into detail why this act is founded on rational principles because a market for kidneys could cause greater damage than good. So now that our market (network) is shut down, how do we address the issue of the shortage of kidney donations? Economist Alvin Roth, Tayfun Sonmez and Utku Unver have come up with a novel solution: create a new type of network.

These economists along with Francis Delmonico and Susan Saidman have developed a kidney exchange network database to help abate the kidney shortage dilemma. Roth and others likened the solution of the kidney shortage problem to a problem faced by many college students in dorms. Some have dorms, some don’t, and some are willing to trade. The same issue appears in kidney donations. For example, let’s say that my brother needs a kidney donation. I have two kidneys and can live with only one, so I go to my doctor and see if I can be his donor. I get the blood test and find out that either we do not share the same blood type or that he will have an immune reaction to my kidney. Our doctor puts him on the wait list and forgets all about the prospects of my being a live kidney donor. However, with the implementation of this kidney exchange program, the story doesn’t stop here. My kidney might not be compatible with my brother, however, it may be compatible with many other persons in dire need of a kidney. Better yet, they might know someone whose kidney is not compatible with them but it completely compatible with my brother. Under the new system, the doctor would not just disregard my prospects of being a donor as before. He/she would submit my medical information into a giant kidney database. My data would be analyzed to find the best match for my kidney and in return, my brother would use the same database to find the best match for his kidney. The article notes that in addition to its possibilities of increasing live kidney donations, the exchange program provides incentives to compile the best information on each donor and recipient thus reducing the amount of organ rejections.

There are, of course, obstacles to the program’s full success. One necessary condition is that the transplant has to occur simultaneously. Imagine the future of the program if I say that I would donate my kidney then conveniently change my mind after my brother receives his transplant. Despite this limitation on the program, in September 2004, the Renal Transplant Oversight Committee approved the establishment of a donor tracking system for kidney exchange. The program is still in its initial phases, but Roth proposes that the program could increase the number of live donations by 2,000-3,000 per year. As of the 2005 article, exchanges existed in New England, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Michigan.

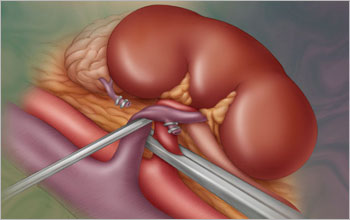

The kidney exchange program discussed in the article provided a tangible example of many of the concepts taught in class as well as ideas in The Tipping Point and chapter 2 of the “Networks” text. First of all, it is clearly evident that this database serves as a gatekeeper between a donor and donee. Let’s say the match for my brother is a 35 year-old businessman from Michigan. The edge, in this case, is the kidney donation. I speculate that even if my brother were to interact with this man, the notion of a possible kidney swap would fail to come up in conversation. However, my brother is linked to the database through my kidney donation, the 35 year-old businessman is linked via his kidney donation and the database is what determines our ultimate interaction. Also, a supplementary concept discussed at the end of chapter three is relevant to the kidney exchange. This is the concept of “betweeness.” According to the text, a node “b” is between two other nodes “a” and “c” if it lies on some shortest path between “a” and “c” and is not equal to them. “Betweeness” is a measure of for how many unordered pairs of nodes this occurs. Clearly, the kidney exchange database would have a “betweeness” value in the thousands. Such a property is of integral importance when considering the temporal element of kidney transplants. By reducing the distance of the connection between a donor and donee (hence the wait time for a transplant) this program could save many lives based on time savings alone. Finally, the kidney exchange database provides a good example of a social-affiliation network discussed in chapter 2 of our text. Social affiliation networks consist of edges representing relationships as in a social network and edges representing participation in activities as in affiliation networks. For example, there is an edge connecting me to my brother and our doctor that represents a social relationship. In addition to these edges, there is an edge that connects me to the database linking me to the kidney donation activity. Imagining what this network would look like graphically is quite a feat especially because there is a clear directional component to it. However, the article does provide a diagram of the main idea behind the kidney exchange program. This program is just one example of how networks can be used not only to model the way the world is now, but also change it for the better. In The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell describes Robert Horchow as one of the ultimate “connectors” in the social realm. I believe it’s clear that this database can serve as the ultimate connector for those in need of kidneys.

Link to Article

http://www.nsf.gov/discoveries/disc_summ.jsp?cntn_id=104404&org=NSF

October 5, 2005

S2N Media for the National Science Foundation  An exchange performed because of blood type incompatibility. The husband of Recipient 1 donates to Recipient 2 and the adult child of Recipient 2 donates to Recipient 1.

An exchange performed because of blood type incompatibility. The husband of Recipient 1 donates to Recipient 2 and the adult child of Recipient 2 donates to Recipient 1.

Credit: S2N Media

Neat! Although I think the laundry detergent comparison is a bit of a stretch.

Of course, this is exactly how a monetary economic system works. It is trading one resource for another. Money is very useful because sometimes you want something but don’t have anything the other person wants; or you do, but there’s no easy equivalent trade.

In this case, kidneys are pretty equivalent, so trading can be done effectively. Still, it’s really no different than using money, except that it prevents people from making a kidney equivalent to anything but a kidney. This really sucks for you if you don’t have anyone that loves you enough to give you a kidney. In this case, money can’t buy you love… or your life.

Still, this is a great improvement if you are lucky enough to have caring relatives.