It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a play or novel or film nearing its conclusion must be in want of a dénouement.

Well, perhaps not universally acknowledged, but whether or not we know the term for it we expect the play we see or the story we read to come to a certain completion: plots untangled, tensions played out, couples joined in marriage or enemies joined in death. We expect a dénouement, a moment where the work resolves the conflicts and events that have been propelling the action and arrives at a certain final harmony. (It doesn’t matter if this is a necessarily positive harmony. A work in which everyone ends up killing each other still arrives at sort of harmonious conclusion: there’s no tension if everyone is dead.)

This sense of harmony, while by no means reducible to by any sort of network theory, nevertheless proves deeply linked to what is essentially a sort of structural balance. Like any group of “people,” the characters of a play or novel or other work can be looked at as a social network, one which changes over time as the work progresses and which should follow all the tendencies of a real social network, including that of structural balance. Tensions between characters along the different edges warp and wane as the plot progresses, motivate the action, and otherwise drive things forward. Resolving the plot necessitates also resolving these tensions, and so we should expect a dénouement to be as much about achieving structural balance among characters as the resolving the events stemming from it.

More importantly however, this final structural balance would seem to lean much more heavily towards one-group rather than two-group solution. Either by altering relationships between characters or eliminating nodes all together (either by death or just dropping out of the story) dénouement tend to result in a single unified group instead of two mutual opposed ones. The Importance of Being Earnest, like most comedies ends with everyone getting along and getting married, bringing everyone together to a single balanced group. Elizabethan revenge dramas end with almost everyone implicated in a negative edge dead, eliminating everyone impeding overall balance. Dickens, Sophocles contemporary romantic comedies, all seem to follow this general trend.

This holds for many works–in fact I would argue it describes the vast majority of conventional Western comedy and drama–but for clarity and simplicity sake, I’d like to switch to a more specific, representative example. It will be much clear and more manageable if we do.

Let’s take a moment then to look a one, relatively simple case in point: William Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Perhaps not the most exciting of choices, but the main plot’s small cast and the abruptness with which relationships between its characters change make it a much more manageable choice than most.

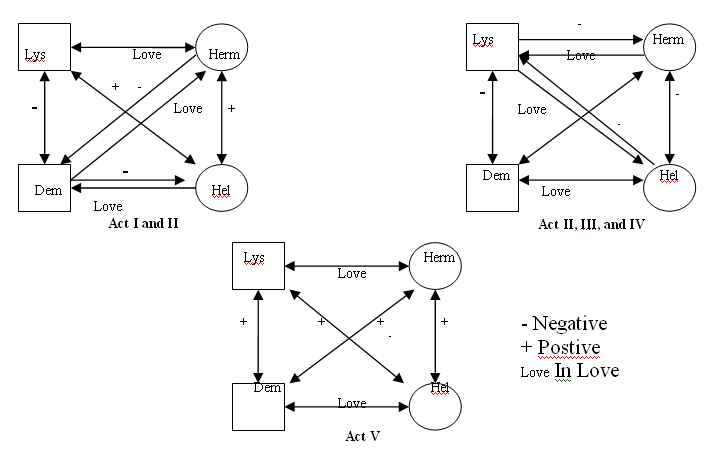

If you’ve forgotten, the main plot of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is pretty straightfoward: Enter two pairs of young lovers. Two of them, Lysander and Hermia, are a couple. A third, Demetrius loves Hermia, who hates him. The fourth, Helena, loves Demetrius, who hates her. They all end up in the woods at night where a fairies drug them, making them fall in love with different people. They fight, until they fall asleep. The fairies drug them again making them all fall in love with the right people. Everyone gets married and lives happily ever after. This gives a pretty simple, three-stage social network in which the tension inherent in the original setup is resolved as the play reaches its conclusion. (See the associated diagram below). You could chart the development of almost any work, but Dream’s smallish central cast and clear divisions make it an unusually easy task

This observation is by no means universal. There are plenty of works which do not resolve themselves, either deliberately or simply by happenchance, and there are others which do resolve themselves but in completely different manners, but this does describe a certain type of plot, most obviously, perhaps, in traditional Western comic (and to a lesser extent tragic) theatre, a type of plot which often serves as a point of comparison for most literate Westerners, extremely well.

* You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.