The investigation of networks is not only applicable to the human population, but also to animal populations. The emergence of distinct groups within populations of wild animals is used to distinguish new species. The in-class example of isolated groups of the human population not connected to any “giant component” is precisely analogous to Darwin’s studies on island animal genetics (albeit not on an evolutionary timescale). Geographic isolation accounts for three of the four modes of speciation (Allopatric, peripatric and parapatric). These rely on the effects of habitat fragmentation or bottleneck effects, and are thus easily explained by fragmentations of a network.

The fourth kind of speciation, called sympatric speciation, is where populations diverge genetically while inhabiting the same region. This rare phenomenon is speculated to be occurring within the world’s most widespread marine mammal population, that of wild orcas (Killer Whales).

In representing the animal populations as networks, what do edges represent? In the human population, we consider an edge the availability of communication. In the natural-world network of the orca population, the relationship between two nodes could be defined by similarities in behavior. Cetaceans are one of the few orders of animals to exhibit creative behaviors, which are then assimilated by offspring and other individuals.

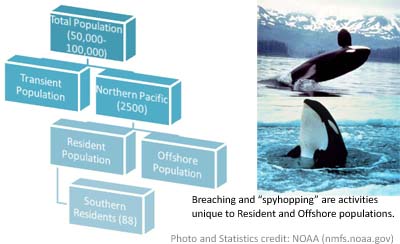

Researchers have defined a few broad sub-components of the wild Orca Population:

- Resident populations stay in certain coastal regions and generally consume salmon. They live in large “matrillines” of several generations traveling together with a common female ancestor. Their vocalizations are population-specific and they exhibit extensive surface behavior, such as breaching and spy-hopping. Genetically they are related with similar coloration patterns and fin shapes.

- Offshore populations inhabit waters farther from the coast and also feed on fish, but congregate in large groups of 20 to 200 individuals.

- Transient killer whales have the largest geographical range, overlapping with the other two types, and have larger dorsal fins. They also are more conservative in surface behavior and feed exclusively on other mammals, such as dolphins and seals.

Scientists are unsure of what to make of these discrete components within the population. Is it simply variance in heritage and morphology, or is it evidence of the emergence of a new species? Another unanswered question is if there is reproductive isolation within each sub-population. To what degree do individual orcas interact or reproduce with other populations?

The National Marine Fisheries Service is attempting to get one population, the Southern Resident population near Puget Sound, off of the Endangered Species List. This population of only 88 individuals was discovered to be separate because of a specific diet and a range limited to coastal North America. The recognition of this discrete group is vital for targeted conservation efforts, as resident groups, compared to transient populations, are especially vulnerable to habitat loss and extinction.

For more information, visit the NOAA Fisheries site on Killer Whales.

* You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.