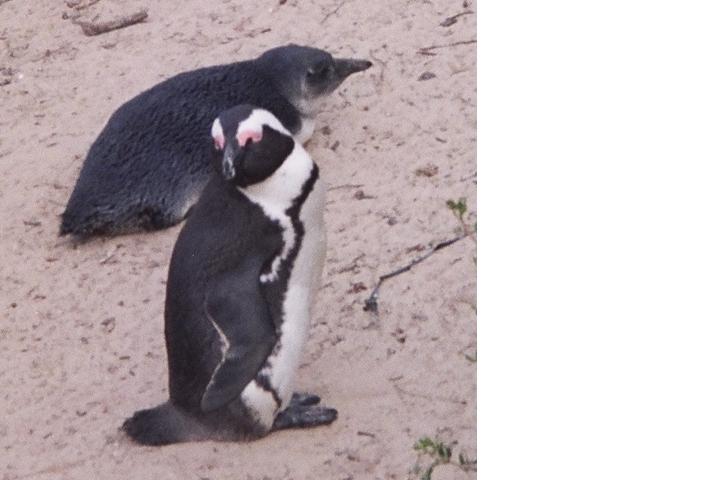

Did you know that there are 17 species of penguins, and that only a few of those 17 call Antarctica home? While visiting South Africa, our tour guide suggested a stop at Boulders Beach to see the penguins. Penguins? In Africa? The idea seemed laughable, but a short walk down the boardwalk revealed hundreds of “jackass” penguins, aptly named for their braying call.

Did you know that there are 17 species of penguins, and that only a few of those 17 call Antarctica home? While visiting South Africa, our tour guide suggested a stop at Boulders Beach to see the penguins. Penguins? In Africa? The idea seemed laughable, but a short walk down the boardwalk revealed hundreds of “jackass” penguins, aptly named for their braying call.

Properly known as African penguins, they live and breed on the coast and off-shore islands. You can see many videos of these penguins on YouTube — here are two of my favorites: Boulders Beach penguins and a “jackass” penguin braying just like a donkey.

Back at the visitors’ center, my misconception was further challenged. Informational displays showed a wide distribution of penguins throughout the Southern Hemisphere - Africa, the Galapagos Islands, South America, Australia, New Zealand, and yes, Antarctica. This interactive map shows the distribution of all 17 penguin species.

It seems that March of the Penguins and Happy Feet only tell part of the penguins’ story. Furthermore, searches for children’s books and lesson plans on penguins primarily focus on those found in Antarctica. No wonder kids (and adults) are confused!

Why teach about penguins?

So why should you fit yet another topic into your already overcrowded science curriculum? Consider this: teaching about penguins may allow you to fulfill standards that are already required. Need to teach about animals’ characteristics, habitats, or life cycles? Does your upper elementary curriculum include studies of reproduction, heredity, or structure and function of living organisms? Or maybe you need lessons on adaptation. Why not use penguins to convey these ideas?

The National Science Education Life Science Standard states that K-4 students should develop an understanding of the characteristics of organisms, life cycles, and how organisms depend on their environments. Can studying penguins and their habitat meet these standards? Absolutely!

The NSES says that students in grades 5-8 should develop an understanding of structure and function in living systems, reproduction and heredity, regulation and behavior, populations and ecosystems, and diversity and adaptation of organisms. Again, teaching about penguins can fulfill these requirements. Additionally, a unit on penguins can also address larger ideas such as how human activities and climate change can impact penguin populations worldwide. (Read the entire National Science Education Standards online for free or register to download the free PDF. The content standards are found in Chapter 6.)

Teaching about the wide variety of penguin species is a great way to capture student interest and target common misconceptions. The theme also easily incorporates literacy skills, geography skills, and mathematics.

Teaching the Science

The SeaWorld Education Department has developed downloadable Teacher’s Guides (pdf files) on the topic of penguins. Each guide includes goals, objectives, vocabulary, hands-on activities integrating science, mathematics, art, and language, and assessment ideas.

In the K-3 unit, students:

unit, students:

Learn about the variety of penguin species

Create a journal to record facts about penguins

Kinesthetically map the locations of various penguin species

Create a penguin to study adaptations such as coloration

Imitate the locomotion style of penguins

Work cooperatively to create food chains and webs

Simulate an oil spill, its effects, and clean-up

In the 4-8 unit, students:

unit, students:

Learn about the variety of penguin species

Create maps to show areas inhabited by each species

Create penguin eggs from soap and hatch the penguin inside

Test and compare their ability to jump to that of a penguin

Investigate the insulating qualities of trapped air and feathers

Some activities in the 4-8 unit require mathematical skills that may be too advanced for fourth and fifth grade students. Use these with students needing extra challenge, or omit these altogether.

In addition to this unit, you may want to utilize web resources. The site Penguins Around the World provides a kid-friendly interactive map, an introductory slide show, an online treasure hunt for penguin facts, and two online quizzes.

Suggested Readings

No elementary unit would be complete without suggestions for supplemental reading. Use these books for independent reading time, a class read-aloud, or create a penguin center where students can extend the knowledge gained throughout the unit.

Many wonderful books have been written about penguins. You may already have some of these in your own personal collection, or you can ask your media specialist to help you locate titles. Rather than provide an extensive list, we’ve chosen to highlight a few award winners here.

Antarctic Ice. Jim Mastro and Norbert Wu. Illustrated with photographs by Norbert Wu. Henry Holt. 2003. 32 pp. NSTA Outstanding Trade Book (2004). Recommended ages: Elementary.

The Emperor’s Egg. Martin Jenkins. Illustrated by Jane Chapman. Candlewick. 1999. 29 pp. NSTA Outstanding Trade Book (2000). Recommended Ages: Elementary.

A Mother’s Journey. Sandra Markle. Illustrated by Alan Marks. Charlesbridge Publishing. 2005. 32 pp. NSTA Outstanding Trade Book (2006). Boston Globe-Horn Book Honors (2006). Recommended ages: Elementary.

Mr. Popper’s Penguins. Richard and Florence Atwater. Illustrated by Richard Lawson. Little, Brown Young Readers. 1992. 138 pp. Newbery Honor (1939). Recommended ages: Elementary.

My Season with Penguins: An Antarctic Journal. Sophie Webb. Houghton Mifflin. 2000. 48 pp. NSTA Outstanding Trade Book (2001). ALA Notable Books for Children (2001). Robert F. Sibert Information Book Honor (2001). Recommended ages: Elementary.

Penguin Chick. (Let’s-Read-and-Find-Out Science series). Betty Tatham. Illustrated by Helen K. Davie. Harper Collins. 2002. 40 pp. NSTA Outstanding Trade Book (2003). Recommended ages: Elementary.

Puffins Climb, Penguins Rhyme. Bruce McMillan. Voyager Books. 2001. NSTA Outstanding Trade Book (1996). Picture book. Recommended ages: Emerging readers, Primary.

Literacy Connection

K-3 students can listen to these books as a read-aloud, read independently, or with a partner. They can record facts in a journal or select new words to create a word wall. A science unit on penguins could also simultaneously introduce students to non-fiction text. Students could browse non-fiction books about penguins as well as selected web resources and create Question and Answer books.

Older students can use the non-fiction books to practice research skills. Instead of an individual report, you could create a class ABC book displaying students’ collective knowledge of penguin species and related vocabulary. Education World provides an explanation of ABC books along with samples of student work. ReadWriteThink provides guiding worksheets and a rubric for assessment.

Narrative text can also be used in conjunction with a penguin unit. Students can keep journals while reading Mr. Popper’s Penguins. A detailed instructional plan from ReadWriteThink includes journal questions and background information.

Back to You!

What about you? Do you have a favorite penguin resource, lesson plan, or book that you’d like to share? What about exemplary student work (without identifying information, of course)? This site won’t be at its best unless we have input from you — the people who make these ideas come alive to your students everyday! Please post a comment to this blog with suggestions, tips, or comments.

And of course, please check back often for our newest post, download the RSS feed for this blog, or request email notification when new content is posted (see right navigation bar).

That’s all for now! Until next time, stay cool with this hot topic!

photograph by Giles Shaxted

photograph by Giles Shaxted

Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Twitter

Posted in Topics: Education, Polar News & Notes, Professional Development, Science, Technology

No Comments