Wikipedia Synopsis of “Guns, Germs and Steel”

In his award-winning book, “Guns, Germs and Steel”, author Jared Diamond attempts to understand and explain why it seems certain cultures throughout the world (and throughout history) have dominated others with their culture and wealth. In his own words, why some have more and others have less. Diamond claims non-bias and tries to avoid making any assertions that could be grouped with racial superiority opinions. Instead, he views the resultant state of the world as a confluence of pre-conditions that brought about changes at different times across otherwise similarly positioned peoples. Diamond belives that agriculture, geography and germs were extremely important and differentiating factors that gave certain civilizations particular developmental advantages. For example, settled agriculture allowed for the development of non-production societal jobs, where some members of a community could forego hunting and gathering. Specialization in turn bred many inventions in social structure and human endeavor.

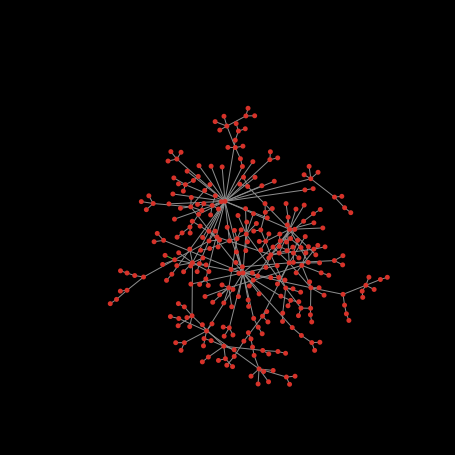

Diamond’s methodological analysis of the confluence of agriculture, geography and germs may be related to our discussion of symmetric breaking: otherwise equal groups of people with similar interests and abilities are eventually differentiated by fluctuations in their pre-conditions. Variations in agriculture, environment (geography) and germs around the world tip similar populations down very diverse paths. Like Schelling’s neighborhood example, even symmetric groups with identical and seemingly unobtrusive desires can become segregated simply by their environs (neighborhood or agriculture/geography/germs). Also, like the examples discussed in class, segregation theories can be very controversial: inferring causation from the resultant data can lead to extreme and incorrect conclusions about populations. Diamond has received heavy criticism from all sides, especially that he may be providing a geographic and environemtal justification for Eurocentric supremacy. It is, I think, incorrect to believe in Euro-centric supremacy – even if you use environmental justification. My understanding is that Diamond’s point is not to say that Europeans or Africans or Asians (or their civilizations) are better or worse or ill-positioned, but that some differences pointed to as “defining” are really not inherently characteristic – and that these differences are the result of some kind of symmetric breaking.

Posted in Topics: Education

No Comments