Quick, picture DNA. Chances are you’ll call to mind a diagram you’ve seen meant to represent this microscopic ‘blueprint of life:” twin helixes running in opposite directions and connected by horizontal bars.

But what if you’ve never seen such a diagram, and indeed never will? What if the sense upon which so much of science teaching and learning relies—seeing—is not available to you?

Dr. Christina Reynaga Peña—a Mexican research mycologist on leave from Mexico’s CINVESTAV (The Center for Research and Advanced Studies) and spending a year at Berkeley’s Lawrence Hall of Science—asked herself that same question a few years back, when she was charged with teaching basic biology to children from a school for the blind.

“Most of the popular activities [to teach biology] are 90 percent visual,” she says. “I felt quite uneasy about not having something interesting and appropriate for the visually challenged students.”

She and her colleagues did prepare a few activities for these learners, but were unsatisfied with the outcome. The seed had been planted, though, and when Dr. Reynaga later met Isaias Hernandez from the Museo de la Luz (the Museum of Light, at the Autonomous University in Mexico City, or UNAM) at a conference, she was fascinated by the activities he and his team had created for blind students.

“His work inspired me to create our own models for teaching biology to blind children,” says Dr. Reynaga.

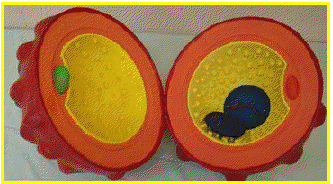

At CINVESTAV, Dr. Reynaga created 3-D models to teach biology and produced a series of DVDs showing teachers how to lead science workshops on plant and fungal biology topics. “We have kinesthetic materials, for instance, to teach about cells,” Dr. Reynaga explains. “Their parts, their shape, their function, the differences among them, and how they form tissues.”

The workshops are for all students, but owe a debt to Dr. Reynaga’s work with blind learners in that the learning strategies employed engage as many senses as possible. Not only do the workshops use hands-on activities and 3-D materials, they also encourage the use of edible and/or scented materials that engage learners’ senses of smell and taste.

Try this at home

Any educator can begin to incorporate sensory strategies into his or her teaching, says Dr. Reynaga. She encourages teachers to pretend for a moment that they themselves are blind. “If you do the exercise of being blindfolding for a few minutes, you can feel how your visually impaired students perceive the world, and then come up with new, multi-sensorial ways of teaching that are suitable for all students.”

Where can you find examples of these models and activities? Watch this space. “Our web page will be updated soon to include them,” says Dr. Reynaga.

In the meantime, close your eyes. Let go of the visual, and imagine how you might engage all five senses when you teach kids about science.

Bay Area is science heaven for parents and teachers

While at the Lawrence Hall of Science, Dr. Reynaga is exploring new ways to measure science learning, especially methods that take into account tactile and kinesthetic approaches to hands-on science. She’s also working with howtosmile.org, assessing the site’s Spanish language activities and helping to locate more hands-on science activities suitable for blind and visually impaired students.

Though she and her daughter, who is 18, and her son, 11, are still getting settled in their temporary home, already Dr. Reynaga is impressed by the informal science learning possibilities in the Bay Area. “With several museums and science centers within a short distance,” she says, “this feels like heaven for parents and teachers concerned about the science education of their children. And web resources are state of the art, so it all comes down to a matter of will.”

In contrast, she says, in the Mexican state of Guanajuato, where she worked for a time, there are just two science museums in the entire state. “And I have to say, we are privileged; some states do not have any! Large areas are economically and educationally underdeveloped, plus a good part of the population does not have access to internet or does not know how to use it.”

Response to Dr. Reynaga’s work in Mexico

Dr. Reynaga’s work has been featured in the Mexican press, on Azteca TV, Yahoo Mexico, and in articles in Guanajuato’s Correo newspaper and in Wawis, an online magazine in Mexico City. Dr. Regnaga herself won recognition in 2007 as an “Inventor and Innovator” in a program sponsored by Mexico’s National Women’s Institute, the Ministry of Economy, and the Mexican Academy of Sciences.

Photos:

1. Dr. Reynaga and visually impaired students, learning about fungi in everyday life

2. 3-D model of ovule

3. 3-D model of a cell, made of fabric

* You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.